“According to one survey,” said Arthur C. Brooks1, “more than half of young people today say they want to be an influencer”.

“We live in an age of loud egos,” he said.

Apparently, there’s been a huge increase in the number of people with narcissistic personalities. This couldn’t just be social media’s fault. Something was happening culturally too, but new technologies had definitely encouraged an amplification of narcissism and now we’d an entire class of professionals called “influencers” who were dedicated to broadcasting themselves, whose goal was to be noticed by others. This explosion of loud egos, Arthur explained, had also coincided with declines in well-being. Such intense focus on self, it seemed, was a major source of unhappiness.

“Success is being seen,” said Belle Tindall2.

She was talking generally about how society measures it, but also more specifically about the celebrities at the most prestigious event in fashion, the annual Met Gala in New York. The more ridiculous their ensemble, the more likely they’d be to grab the headlines the next morning. It didn’t matter if they couldn’t walk in their outfit, sit in it, breathe in it. As long as they were seen in it. “We’re teaching ourselves that if we’re void of attention, we’re void of significance,” she said.

There is one question that people commonly ask me. “Do you think you did the right thing?” they say.

They want to know if I regret leaving a career and a title and a status and a regular salary to blunder about trying to find myself for a while and then emerge with a book that has sold less than 200 copies. Perhaps they have doubts about whether this journey has elicited the correct results. Their question presupposes there is always a right and a wrong, that we can be certain taking the road less travelled made all the difference when we don’t know where the other road led. It also presupposes I should be able to provide some evidence of successful decision-making.

Last week when asked this, I decided I needed to get my story straight because I was somewhat underwhelmed by my answer. “I’m much happier,” I said. “That sounds a bit simplistic,” I added apologetically. Happiness, it’s just so … vague. What did I mean? Why was I happier? And then, I ad-libbed for a while.

I was more balanced. My life quadrants were aligned. I was emotionally, mentally, physically and spiritually satisfied. I had complete control of my time. I exercised regularly and didn’t have to squeeze it in at dawn. I prioritised sleep and solitude. I avoided busy. I had streamlined my obligations. I did whatever I had to do to eliminate resentment. I had boundaries, massive impenetrable ones. Reading and resting and doing absolutely nothing weren’t add-ons, reasons to feel guilty, unproductive interludes. They were essential daily activities. Best of all, I had found my calling, and I had permission to do it. To do it well, I had to pay attention to the human condition. I’d discovered there was a gap in the market for non-judgemental listening, that this was what made people feel seen.

But yet, in theory, on paper, there was also so much I’d lost. Being happier had come at a cost.

I was reminded of this recently when I applied for a role on a board, an unpaid one, one I would be doing for the love of it, meetings I’d be attending for pleasure. I’d been a trustee before. I’d even been a Chair. I reckoned I was a decent candidate. There was an interview dressed up as an informal chat. Then, I got the email to tell me that whilst I had an impressive CV, I didn’t have the skills they needed. I joked about it at home, how I’d stepped so far out of the working world that I couldn’t even get a voluntary position. But it was a sobering moment. Stepping back in would be a challenge. By choosing to, in effect, disappear, I had handed back my relevancy. I’d wiped out twenty years of effort.

“Our value diminishes the longer we dwell in obscurity, anonymity is nothing short of self-sabotage. That’s what we’re subliminally telling each other,” said Belle Tindall.

But there was nothing subliminal about it. It was the reality. Visibility is rewarded. Therefore, what we are primed to fear most is invisibility. “A need to be seen is written into the rock of my being,” said Belle.

This yearning to be seen. This attaching it to our value. What was it doing to us? Those who want to be noticed aren’t just on virtual platforms. They’re in my physical spaces. They’re all around me, everywhere. And they’re not bad people. They’ve just accepted a system. They’re playing the game. To be seen, they must put on a performance, be better than everyone else, prioritise individual achievement. They must show up and hype up and suck up to those who hold power. But it also means, they must be careful. It’s best to comply, sit on the fence. It’s best not to speak out in case it jeopardises a future. It’s best to live with the niggles of what am I compromising on to be seen.

From time to time, I remember that I’ve written a book, and I’m supposed to be promoting it, or sharing the reviews I haven’t got3, or asking celebrities to endorse it. I’m supposed to be figuring out why it still doesn’t appear when I search on Amazon. I’m supposed to be trying much harder to be seen.

“You know how people are always talking about hustling and grinding and manifesting and vision-boarding their way to success?” said Michelle J4. “Well, I've developed a revolutionary alternative approach that I'd like to share with you all today: sitting very still and doing absolutely nothing until opportunities materialize out of thin air”.

This could be considered a complete lack of initiative, she said. But she preferred to think of it as “strategic patience”.

“I'm simply allowing the universe time to get its act together and figure out what it wants to do with me,” she said.

I liked it. It was kind of my strategy too. Why was I happier? Yes, it was all those things I’d mentioned but they were just outcomes. It was mainly because I had quit the striving to be seen. But I wasn’t out of the woods yet. It was a continual irk that writing wasn’t enough. I needed to be read too.

Arthur C. Brooks suggested cultivating a quiet ego as a coping mechanism. That was the secret, he said, to staying happy in a culture that was always shouting at you to be seen. Quiet egos placed less importance on self. He had a plan. It included asking himself this question. “What do others need that only I can provide?”

This empowered him to do what was uniquely his to do.

“Only I can be a husband, father, and grandfather to my family - because I am by definition those things already - so I focus on doing those jobs generously and well. Likewise, only I can teach my class and write my column today, so I pay attention to performing these tasks to the best of my ability”.

What do others need that only I can provide? I guess only I can be a wife, mother, daughter, someone who produces this to the best of my ability.

But did I mention this book I’ve written…

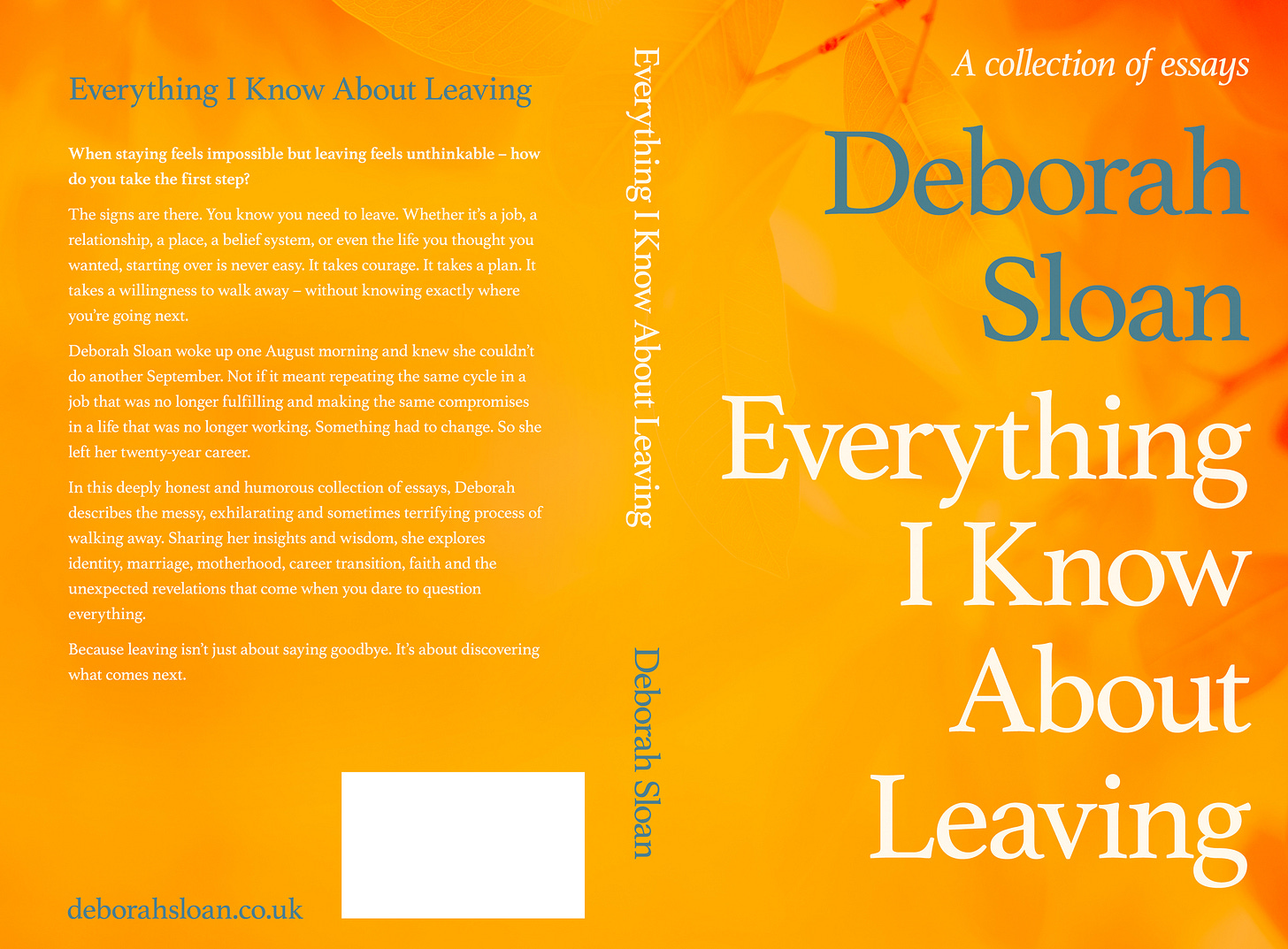

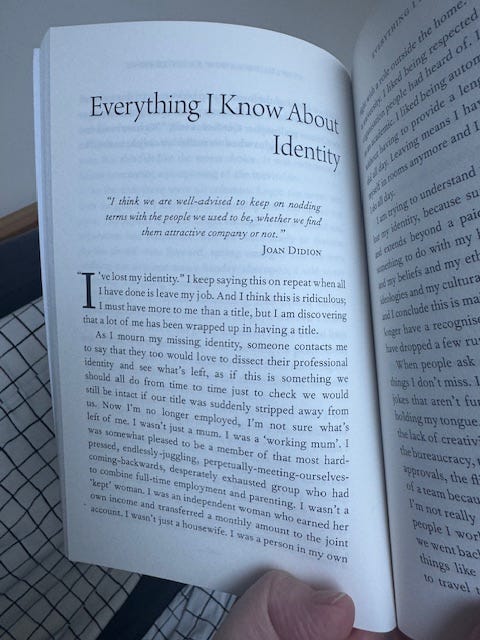

Here’s a taster of the chapter on identity where I explore losing mine and even more stuff about being seen. You can buy a copy on Amazon. Other options available on my website.

Please do write one if you feel inclined to…

Thanks for that post Deborah. You ask many a vulnerable and valuable question - for which I too have not an answer. We will just have to keep blundering on...

I finished reading your book this morning! Yes you should promote it, get a plan, and get to it!