Sometime during the second week of December, when my thoughts had not yet turned beyond me to what I would gift everyone else during the season of gifting and when I was only anticipating rather than living through the post-Christmas psychological hangover and when I wasn’t yet filled with lethargy, self-loathing, unfulfilled potential, and a desire to urgently cleanse, detox, get back to normal and get the bins out, I bought a notebook. It was a vibrant yellow, medium quarto, embossed with all four of my initials, capitalised in silver, bottom left-hand corner. It was unlined because I refused to be bound by ruled structures. It was expertly hand-crafted in the English countryside by a company proud to use the word notebook in their name. Its high-quality British milled paper was not only fountain pen friendly but opaque and smooth to the touch. It was perfect. I didn’t want to mess this one up. I wasn’t sure I was worthy of writing in it. I decided I would get a fountain pen.

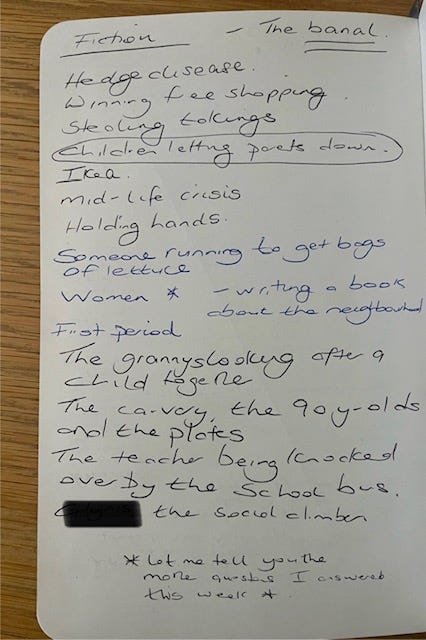

It wasn’t my first notebook. During previous second weeks of December when I’d decreed that the next year would definitely be my year, I’d purchased other notebooks, a fern-green one which made me think of forests filled with the earthy scent of damp or whatever it is that forests smell of, the one that turned out to be a putrid shade of blue nothing like its photograph, the one where I’d chosen gold lettering because I needed a change but it just wasn’t me, the tropical orange one with the leather cover that taunted me with its accusatory fingerprints. You see, in 2021, I was going to write a novel. In 2022, I was going to write one too and again, in 2023. I’d heard it took at least twelve months, but I’d never managed to get started and I’d never used any of those notebooks for their intended purpose. There was that lengthy journey through the Bible course, the six-week one on the dangers of motherhood and the one about being a pilgrim which I’d hoped would explain my peripatetic restlessness but was mainly about ranting under the influence of the Holy Spirit. The notebooks became tainted by their failure to be the right notebook. Gradually I got rid of them. When I’d scanned them for anything useful before burying them under the non-recyclables, I’d found insights on Ezekiel and Daniel on the left, scribbles about yoga pants and identity and the Good Friday Agreement and giving blood on the right. It was clear that my mind had been in two different places. There was a page that looked like the initial stages of something – hedge disease, teenagers letting their parents down, teacher being knocked over by the school bus, IKEA, midlife crisis, holding hands.

I had no idea what this novel was supposed to be about. I had no idea if I even had the stamina for it. Sometimes 1200 words on a Friday drives me crazy. As 2024 eased its way in, I marched through the IKEA carpark on high alert, and remembered how I’d thought it would make a great opening scene, all that reversing, drivers with their vision impaired by wardrobes and strelitzias, the pensioner, the crunch, the guilt. I could expand into themes of regret and redemption, how the enforced circuitous walk is the Swedish version of purgatory, the sense of relief when you emerge, how everyone only goes in for one thing, how we only get one life. I caught myself on and bought a milk frother.

“Has she ever thought about writing plays?” said someone to my husband. “I don’t like plays,” I said, all that listening, surrounded by people who think the theatre makes them clever, the interminable dullness, the dread of a soliloquy, the fact you can’t eat to relieve the boredom. I wanted to write something I’d enjoy. I’d do it for all the others who prefer solitude and the corner of the sofa and pulling down their blinds and pretending they’re not in and whose kids know exactly where to find them lounging on a Sunday. I wanted people to say they’d read my 300 pages in one afternoon, in the bath, that they couldn’t put it down, that they’d missed meals or weddings or their knighthoods because they’d been so enraptured by it. I wanted to see people clutching a copy on the Tube, lying on sun loungers, smoking roll-ups in their berets outside cafés, discussing me at their wine clubs. I thought of Neil Gaiman1 being frisked for books as he entered family occasions and how some of us prefer books to humans and how I could be people’s friends without actually having to be their friend. I’d never read any of Neil’s stuff, but he’d poured all his childhood anxieties into his work. Fear stalked his stories - the dark, shadows, witches, anything that did exist and anything that didn’t. I’d write my novel for the people who had fears like the fear of never being good enough and I’d let them know I had that too. I’d write it for all the younger versions of me so I could cry for them now and tell them it would all be ok. I’d tap my readers on the shoulder and say we may be grown-ups but….

I thought about beginnings and endings, how I was hung up on where to start, how I should have started this writing better. “Sometime during the dying embers of”, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”, “Call me Ishmael”. On Radio 42, three people who had managed to publish something said you can rework that first sentence later, just write and figure out the beginning at the end. That’s what matters most - the ending, the last note that rings. Something is fundamentally changed, something has happened, something has been realised. There is the rising of a knowledge that can no longer be suppressed. All the reader needs is surety of tone and to know they’re in safe hands. It was a lot of responsibility. It was what we want in life.

Anne Enright had said the beginning should contain all the fragments of the novel’s DNA. It sounded just like life too, and I thought about how I wasn’t really that interested in plot, how my favourite authors don’t get hung up on plot. They get hung up on life. There doesn’t have to be a twist in the tale. Life is a story that never ends tied up neatly with a bow. Neil Gaiman hadn’t attempted an autobiography. He’d used his novels to infuse a fantastic adventure with details from his own life. “I love the freedom of making things up and I love the fact that you can draw conclusions in fiction. You can take things to places that you can’t ever really take them in real life because you never get closure in real life,” he said. I’d refer anyone who complained that nothing much happened in my novel to Ann Patchett. “How many serial killers do you know?” she’d said. I’d weave in my observations. I’d show how life is always stranger than fiction. I just needed to figure out how I could get away with incorporating the stories I’d collected without identifying anyone who was still alive. “The people that you’d really like to talk to and get answers from are often dead,” said Neil Gaiman. I made a note to ask my parents about all the things that had happened that they didn’t like to talk about.

There were notes on my phone. I’d have to tidy them before moving them to the yellow notebook. I didn’t want to mess this one up. There were lots of notes I’d typed in the salon because all life was happening there. Someone was telling a story – a woman, a man, she’d never met his family, they met at her house twice a week, Wednesdays and Saturdays, they liked to watch YouTube videos, he kept leaving black stains on her pillow from the boot polish in his hair. “Something’s not right there,” said my hairdresser. It sounded more promising than IKEA.

I guess what my yellow notebook needs is a story. I just need to choose how it ends.

Looking forward to what you share in fact and fiction in 2024

Can’t wait to read it!!!