The One Where I Pack A Suitcase And Go To The Algarve To Ponder Midlife

This is a 'long read'. Pondering midlife isn't quick so grab a cup or glass of something and enjoy!

“We had a good year end,” said the man in the open-necked blue shirt to the other man in the open-necked blue shirt. I knew year end was important, but it wasn’t important to me. I just had to get to the end of a good pot of coffee and a novel set in 1970’s Belfast during ‘The Troubles’1. It was supposed to be a heart-breaking story of forbidden love. It didn’t seem possible, but it had apparently broken Marian Keyes’ heart a million times. A fifty-something Protestant barrister is having an affair with a twenty-something Catholic primary school teacher. He is married, defined by the career that ends up getting him shot dead. He smells of soap and tobacco, has a flat in town to conduct his extra-marital relationships. He is never at home. Kissing him is like drinking whiskey. He almost tastes fetid. He turns up when it suits him. She has to wait for him to call, doesn’t know if she is just the latest in a string of entanglements that boost his self-esteem. If that was love, it left me cold. It was April in Spain that broke my heart. Dr Quirke, the Irish state pathologist is holidaying in the Basque Country with his wife, Evelyn2. They are both middle-aged, equals. It’s the 1950s but she has a career to match his. They feast on oysters and each other. He has a paunch, she wobbles. Theirs is a love story. I realised a man had written what love looks like so much better than a woman. She gets shot too, in a hotel lobby. He can’t save her. I wasn’t sure I could deal with the next book in the series, what the ending of that love would do to him.

I was breakfasting alone in a Portuguese hotel. My travelling companion had toothache. I’d spend the next fifteen hours channelling some sort of empathy, wishing I had access to dental equipment, watching her beg for ice cubes, telling her she absolutely could not get back off the flight. More men were arriving, greeting each other. There was a conference3. It was the flagship asset recovery event in the fraud and insolvency practitioners’ calendar. The men were all incredibly busy. They wore their busyness like badges of honour. One had to put his kids in front of a Disney film on a Sunday afternoon so he could get documents ready for Monday morning. I wanted to tell him that before he knew it, they would be watching Grey’s Anatomy in their bedrooms with no need for him. “It’s mad,” he said, “but then what’s the alternative, not being busy, getting the sack?”. “My wife is very understanding about what I do,” said another. It was his fortieth birthday at the weekend. He hadn’t really time for it, but she was organising a party anyway. He just had to turn up. His children were starting to understand his job. “We talk about bankruptcy,” he said. None of them were enthused about the conference dinner but the networking opportunities could make them even busier. I’d watch clones of them all afternoon, strangled by the ties added to the blue open-necked shirts, by the lanyards round their necks, by their professional identities. I’d see the portly man with the curly white hair again. We’d run on neighbouring treadmills at 8am. By 10am, a suit had turned him into someone else. He had a new identity. I was mesmerised. He even had a younger version of him with him, ready to step into his shoes.

I hadn’t planned to focus so much on men during my five-day stay on the Algarve, but I’d become obsessed with them, how they were approaching the various stages of life. I had brought The Midlife Crisis Handbook4 with me. I was pondering how women are quietly prescribed HRT when they present with low self-esteem, how men can loudly get away with faster cars and younger women. I’d met George on the courtesy bus. He was at the hedonistic stage of life, on his tenth gin and tonic. He’d brought his glass on board with him. His girlfriend had saved a child from drowning at the beach, but he’d been a bit too intoxicated to react to the drama. “Do you know each other?” the Dutch girl asked us as we shifted over to make room for her. “Yes, she’s my ma,” he said. When we reached our destination, he’d hold out his hand to help me off. “Lady in the blue dress,” he said. I saw who I was through a young man’s eyes, old. I’d watched the couples on sun loungers too. They were at the unfettered stage of life, entangled in each other, their bodies, as yet unimpacted by babies and homes and the toll of having to make it in life. I’d watched dads with toddlers, seen how they usually weren’t the ones to stick it out by the pool, how the mums laboured most. I wondered how many women would eventually just become understanding wives. I’d found my middle-aged nemesis too. I was determined to outwit the bare-chested German in the gym but no matter how early I got there, he’d already thrown his towel over the cross trainer. The machines were showered with his sweat. My AirPods couldn’t drown out his grunts. My only option was to row until he left, patiently wait my turn. I marvelled at the male ability to not care, to take up space, to remain self-focused, to jump into pools, to front crawl, to cause tidal waves, to lie outstretched in saunas, to be allowed to blaze and strut through their midlife crises.

I’d post a photo of The Midlife Crisis Handbook on Instagram, say I reckoned I’d already had mine. I was out the other side. I hoped I’d done it with grace. The statements which indicated whether I was in the early or middle stages of a midlife crisis described the three-years-ago me. Yes, I had indeed become increasingly aware that I was getting older, that time was running out, that I was lost, bored, anxious that I had under-achieved. On paper, I’d achieved measurable elements of material success, yet I had an overwhelming feeling of malaise. It was just as Dr Hannan described. I had woken up in August 2019 and found there was a mismatch between me and the world I lived in. Carrying on doing the same thing was no longer an option. I determined to write a piece on how ‘46 is a dangerous age’. I agreed with her that lacking meaning in life is one of the greatest existential terrors, that what is meaningful to us changes as we age, and we must adapt to it otherwise we risk dying before we actually die. But I didn’t really want to call what I’d been through a crisis anymore. It had been a midlife review, an identity transition, a positive awakening. I wouldn’t have changed any of it, the clearing out of the dead wood, the releasing myself from unwanted life scripts and rules that no longer served me. I’d found the ‘impasse’ hard, the place where I knew change needed to happen, but I didn’t know what that change looked like. The floating in ‘liminality’ hadn’t been easy either, that disorientating period where I had to consider how I wanted to live my future life. I hadn’t a name for it before but now I did, all those months where I was almost driven insane because I could see no outward movement, when I was bombarded with questions about what I was doing next but had no answers. Hannan called it the ‘fertile void’, the gap between the old and the new lives. She extoled the power of doing nothing, of holding that tension to allow something to flourish and evolve. “There will always be inward movement,” she said.

I was glad I had already recalibrated, settled into the new midlife version of me. From the other side, I could look at everyone else with an experiential wisdom they didn’t yet have. Hannan explained how the biggest regret people have on their deathbeds is wishing they’d had the courage to live a life true to themselves and not the life others expected of them. “The first half of your life is about fitting into the world, the second half is about creating a world that fits around you,” she said.

As I’d glared at the man hogging the cross-trainer, I had also listened to Simon Pegg on Desert Island Discs. He was friends with Tom Cruise. They’d done Mission Impossible III together. They’d been filming in South Africa. Tom decided he wanted to go and swim with sharks. He flew them in a helicopter to a bespoke diving trip. It was a “real Tom Cruise kind of day,” Pegg said. It seemed perfect. He said he’d the life he’d always dreamed of, the Paramount lot, blockbuster movies, the material success but it was difficult because it took him away from home. He missed his family. He could only cope because he knew he had them to come back to. “When are you happiest?” asked Lauren Laverne. “When I’m at home sat in the snug with the family. We’re all on different devices, the dogs are asleep,” he said. Simon was 52. I reckoned he had recalibrated too.

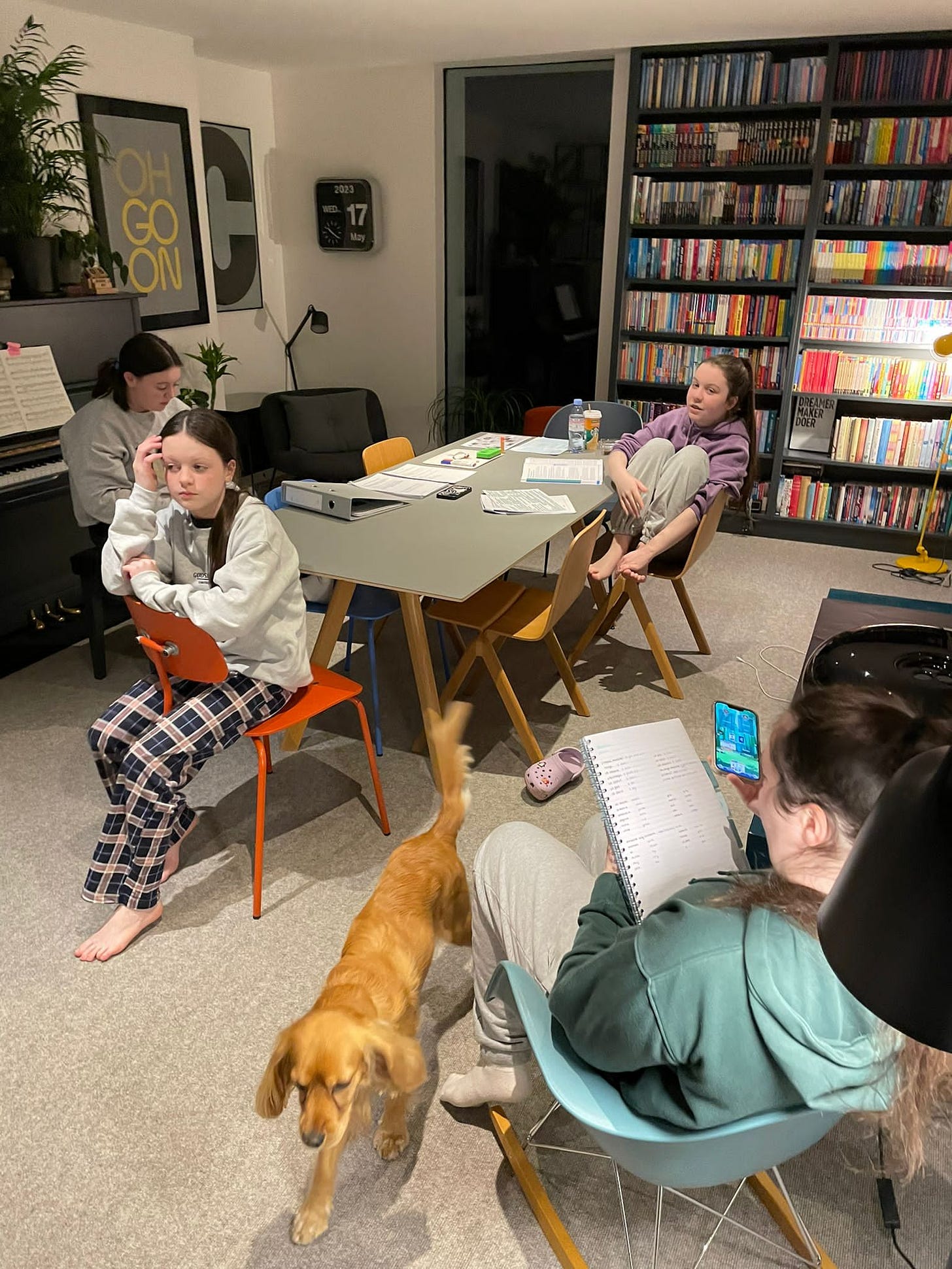

As I emerged from my identity transition, I had an overwhelming urge to travel, not just to the Algarve but anywhere. It took me time to realise it wasn’t because I wanted to have adventures, to be away, to leave anything behind. It was so I could keep coming home. I wanted to miss what mattered most, to have that regular wake-up call, to not forget to be grateful for what I have. “I miss you,” said the middle-aged husband I had left at home. He had sent me an image of our daughters. The dog was there too. I called it a tableau.

As I parted from my travelling companion, wished her well for her dental appointment and walked down the driveway towards the house on a Thursday at 1am, the lights were on. I stopped, set down my suitcase, contemplated the scene. I took a photo to remember that feeling of coming home. In it, I captured the child who had waited up for me. The man who had waited up too made me tea and toast. It wasn’t forbidden love, but it was a good love. I’d probably never have a good year end but I could have a good midlife.

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy

April in Spain by John Banville

For clarity, I wasn’t attending it.

The Midlife Crisis Handbook by Dr Julie Hannan

You always take us on an inner journey with your writing. I am confused though: did you attend that conference and therefore have a new job?

Love this one! No work talk & a people watching adventure. You do miss this place we call home. Absence does make the heart grow stronger.