It has come to my attention that there is very little goodwill in my house.

“That’s not my job,” they say when they walk past the blue bin at the gate or add more dirty plates to the stack on the worktop or leave a load of whites to fester in the machine. In the system known as our home, that responsibility belongs to someone else.

At some point, we, the parents, decided to allocate household tasks to our offspring when they reached the age of being able to handle sharp objects. We thought it would mould them into better humans. But these tasks were not acts of goodwill. Routinely performing them came with the incentive of pocket money. We should have named them chores. Instead, we elevated them to the status of jobs. We made the mistake of attaching compensation to them. We told them work is always rewarded.

The first child maintains that she was the original dishwasher-emptier, but one day suddenly without warning, this role was passed to the third child because it was easier for her. But the third child will only do her job in the morning before she leaves for school. Should an additional evening shift be required, she will not turn up. Someone will have to cover for her. The second child is in charge of waste management. Messages containing the word ‘overflowing’ are regularly sent to her mobile. The youngest child is supposed to set the table, but as her social life renders her non-existent at mealtimes, we usually locate our own forks and spoons. No one is quite sure what the eldest child was promoted to in 2017. The third child believes it is cleaning the kitchen floor which she regularly inspects and deems unacceptable. The eldest child retaliates by saying she is always driving her places to get matchas free-of-charge, and could she not be a bit more grateful.

Were it to be viewed as a microcosm of society, my house could be considered a failed social experiment. If I thought I could establish a cooperative, I was wrong. Why would they simply give and expect nothing in return? They didn’t sign up to this thing called the greater good.

There was a time when I thought everything was my job. When I was less cynical, and more ardent people-pleaser, and powered by self-denial, I was all for the greater good. Need someone to back-translate the Bible, I’ll do that. Need someone to apply tattoos to fifty children in the rain, I’ll do that. Need someone to set up a network to help women fulfil their potential in higher education, I’ll do that. Need someone to join a relay team, befriend the elderly, make a pudding, be the Secretary, produce a newsletter to keep church members connected during Covid, organise a gathering, sing in the choir at Christmas, find raffle prizes, I’ll do that. I am amazed by my former self. She is a stranger, she and her exhausting Protestant work ethic. Something eventually gave. Perhaps it was the triple-jobbing, the domestic, the workplace, the civic contribution. Perhaps it was the lack of reward. Now, I am more Arthur Brooks with his reverse bucket list. “My goal,” he says, “for each year of the rest of my life should be to throw out things, obligations, and relationships until I can clearly see my refined self in its best form”1.

But now I’m not sure what my job is since I willingly gave up regular paid employment and threw out things. When I describe what I am doing, I call it a vocation. But this calling is completely self-appointed. There has been no divine stamp of approval, well not if that comes in the form of results. Saying I am morally obliged to write for the greater good, that I will do my art simply because I believe in it is somewhat indulgent. The reality is I’m doing something no one has asked me to do. The world will continue to turn should I stop. I’m only adding to the content everyone is drowning in. I’m getting used to hearing I don’t work because writing is not a real job. It doesn’t come with any real job trappings, a lanyard, meetings, a structure, outcomes, a payslip. I have joined those who are vilified for not having jobs, the stay-at-home mums, dads too, the ladies of leisure, those whose gifts do not fit the standard 9 to 5. If vocation is meant to make me a better human, I have discovered that my refined self in its best form still requires validation.

And even if writing is my job, I’m not sure what I should be writing about. The successful are the ones playing the game, self-help, commercial fiction, cheap dopamine, clickbait, the secret to…. I wanted people to think. I would pay attention and share what I was seeing, encourage them to see it too. But I’m realising people don’t always want to see. They prefer echo chambers, reinforcement of existing beliefs, challenge avoidance. I am increasingly frightened of offending. I didn’t realise Ben Fogle was so popular until I lost 1% of subscribers after featuring him. “I’d like to gently challenge your narrative,” says someone when I mention the existence of the patriarchy.

I have come to a crossroads. Should I continue with this calling that is bearing little fruit. Was it a failed social experiment? There is a reason Van Gogh cut off his ear in despair. I can see the benefit of having a job that comes with a description and a set of coherent tasks. Something solid to be attached to, to be defined by, to measure the productivity of my days by, to hang my self-worth on. This is luring me back in. Whilst I’m aware that without artists, the story of humanity could remain untold, no one really wants to pay for such insights. And I have only so much goodwill in me.

As I am preparing this, the third child is reading over my shoulder. “Writing about yourself again,” she says. She is three days into her ‘work experience’ in the seat of the Northern Ireland Assembly. We have role-played numerous scenarios. What if they don’t answer when I ring to say I’ve arrived? What if they don’t tell me it’s lunchtime? What if I get lost on the way to the toilet? What if they forget I’m in the Chamber? What do I say if someone tries to take me away in their car? Her seventeen years of existence, how she has been formed and educated, has been channelled towards finding a job, but not just any job that enables her to survive, but rather a career, progression, each thing she does a step towards something more. Ideally, she should be aiming for a profession, one that evidences particular expertise, something that elevates her in the societal hierarchy, something that’s easy to understand, something that realises self-actualisation, an identity.

“You are not your job and soon you won’t have one. The identity crisis hiding inside the job market crisis,” I read in an article2. “This is a story about all knowledge workers,” the writer says. “The jobs AI is coming for first aren’t the ones most people assumed. They’re not manual labour or frontline retail. They’re not cashiers or delivery drivers. The jobs most vulnerable to AI displacement aren’t manufacturing or service roles – they’re the supposedly ‘prestigious’ positions. The lawyers, the managers, the analysts, the marketers. Everyone whose job depends on reading, writing, planning, synthesizing, managing, creating, or communicating. The people we’ve historically called ‘white collar’”.

The writer has a warning for her readers. It’s a familiar one. Start building an identity separate from your work, she says. What’s coming is not just job loss, but identity collapse. The psychological whiplash will be severe. But most people can’t do this, she concludes.

Because we are after all, human. Invisibility does not mould us into better ones. We struggle to operate in relative obscurity. We want to feel useful. We are wired to be seen, admired and respected. Intrinsic motivation can be an elusive concept. We have been told that our work will be rewarded.

“If you reach professional heights and are deeply invested in being high up, you can suffer mightily when you inevitably fall,” says Arthur Brooks. “Whole sections of bookstores are dedicated to becoming successful. There is no section marked ‘managing your professional decline’”. If AI doesn’t get you, it seems mental deterioration will. His advice is to detach from earthly rewards, to walk away before you’re completely ready. His theory is compelling. His sentiment admirable. He followed his own advice by resigning as president of a flourishing think tank. But he kept his column in The New York Times, continued publishing his best-selling books, delivering his well-paid speeches. This was not an identity collapse, at least not like the one I remember experiencing when I left a title, status and salary. It is interesting I should even consider going back.

So, the question is, should I get a real job again? Send me your answers on a postcard or maybe in the form of job ads?

And while I’m at it, what should I be writing about?

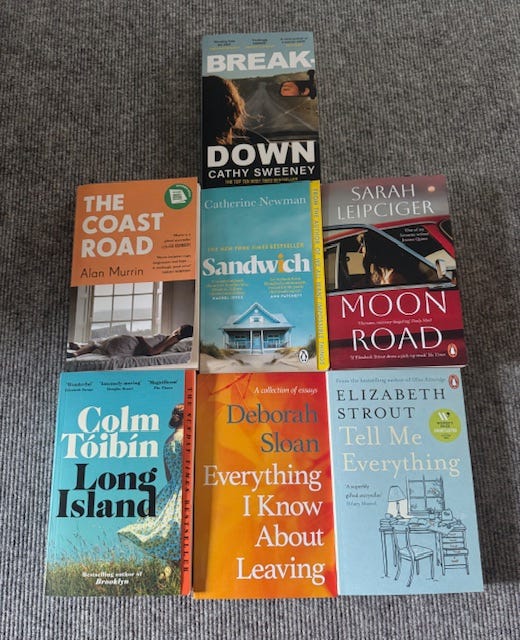

P.S. Maybe my job is to read lots of books and recommend the best. Here’s some suggestions for your summer reading:

This is a great article Deborah. Let’s face it, what constitutes a “real “ job anyway? One that pays a salary? One that has a contract and written job description? One which is in a big company with lots of people? Is the farmer who works the land not in a real job? Or the volunteer who works for free in a charity shop not in a real job?

Putting your mind to doing a task which provides a service and has a purpose is a job from the parents, the carers, the volunteers , the CEO’s, the lollipop ladies/men, the writers etc etc etc

Who is anyone to judge what is a real one or what isn’t …

Keep writing…. You’re pretty darn good at your job ♥️

What an excellent and thought provoking piece. And just so you know, writing is a real job. May I gently suggest that when the next person tells you it is not, that you stuff them into the overflowing waste receptable ......... or the dishwasher.... obviously after it's been emptied in the morning!