There is a photo of my youngest daughter which I can’t stop looking at. “You look Amazonian,” I tell her. “What does that mean?” she replies. And I give her an explanation. Like a warrior, I say, a fighter, strong, capable, determined, maybe a mixture of Moana and Princess Merida. I am her mother. I am somewhat biased. But, in this photo, she is wielding a weapon. It is raised above her head. She is about to bring it down to meet its target. Every muscle in her body is poised. She is powerful, in control. She has been captured in battle, brandishing a hockey stick.

“Can somebody give me a definition?” I ask my daughters. I keep hearing this word. It suffices as a complete sentence. It seems fairly positive. It is appropriate for something that has happened in the past, for something that is happening now, for something that will happen in the future. It can describe a person, an event, an activity, a plan. “It’s kind of like good,” one of them explains. “Sort of a vibe”. “You just know,” they conclude. “Slay”. I will not use this word. I am not in the right age bracket.

I have been watching Adolescence. I’m incredibly late to the party seeing as it’s been around since mid-March. It’s a “runaway success”. It’s gone global. It’s inspired a national conversation, it seems, and not just because of its impressive shot-in-one-continuous-take. Even Keir Starmer has watched it with his teens. He’s met mental health charities to discuss the issues it raises. He’s aware of a greater need for online safety. He’s acknowledged the dangers of the internet. He’s supporting Netflix to make the series available to secondary schools across the UK. But he’s not planning on blanket-banning social media for under-16s. “My experience of teenage children is, the moment you say you can never, ever look at something, then that's the pretty surest route to make sure that they'll find a way to do it,” he said. And I felt a fresh admiration for him. He seemed, all of a sudden, like a well-rounded dad.

If I’m honest, I’d been putting it off, spending four hours analysing why Jamie, a thirteen-year-old boy would murder his classmate, Katie. Then, there would be the deciding who was to blame. Was it his parents, his peers, society in general, or the incels he’d been radicalised by? I’d had to look that one up again, incel, a term used to describe a subculture of involuntarily celibate people unable to find a romantic or sexual partner, who create communities to defame and objectify the women who ‘reject’ them. I’d heard Adolescence was a difficult watch. And anyway, it had already been dissected to death. Like everything else, it had started off scooping up the accolades. Now it had reached the it’s-time-to-bring-you-back-down stage, article after article on what it got wrong. I reckoned I had nothing to add. There couldn’t possibly be a new angle.

“Girls, do emojis have weird meanings?” I ask on WhatsApp. “Yes,” one answers with an image of a sideways face that looks like it’s melting. “What about the different colours of hearts?” I send a blue one as an example. “Ily,” says another. “I’ll pay someone for a lesson in understanding your language,” I say. I get “rizz” in response. I’ve got as far as episode two of Adolescence. It is set in Jamie’s school. The two DIs are conducting interviews. “This is like a holding pen,” DI Bascombe says to DI Frank. The pupils are out of control. There’s no sign of a behaviour policy. The teachers are weak and ineffectual, the female ones merely pastoral, the male ones completely useless at classroom management. There is a lot of shouting. Instagram messages are being scrutinised. The adults are out of their depth. DI Bascombe has to ask his son who barely talks to him for help. They agree to go for chips in an attempt to rebuild their relationship. What Adolescence captures best is the ever-increasing, bewildering generational gap. There is a sense, a small hope, that food might bridge it.

I realise Jamie is around the same age as my youngest daughter. As Adolescence is released, the fifth anniversary of the first Covid-19 lockdown is being marked. In March 2020, eight and nine-year-olds, the ones who are now thirteen and fourteen, were suddenly forced to move into a virtual world. There they would get their schooling, their socialisation, their development, live out a spring, a summer, an autumn, a winter. Then we told them to exit it again and return to the real world without ever considering the consequences.

There’s something annoying me about Adolescence. I consider whether it has got the education system wrong but Google tells me otherwise. It is really that bad. ‘Adolescence has a woman problem’1 is a headline in The i Paper. I knew I had nothing novel to add. How the women are portrayed, I reckon, is what’s bothering me but someone else got there first. “I’m loath to do down a TV series that’s sparked a vital conversation,” says the journalist, “but I can’t help noticing, while so many of its men are fully fleshed out, too many female characters have not been fully drawn”. Perhaps, she concludes, this series created by two men, might not be intended for women. Manda, Jamie’s mother, is hysterical, prone to victimhood. Mrs Fenumore, who guides the detectives around the school, is complacently ignorant with no knowledge of incel ideologies. Jade, Katie’s best friend, is aggressive, with a bizarrely transactional view of friendship. Katie herself may have bullied Jamie. That’s why he did it. The old trope is wheeled out. She brought it on herself. We learn nothing about DI Frank as she hovers in the background, playing second fiddle to her colleague whose indigestion gets more airtime than her inner thoughts.

“75 per cent of teachers are women, indicative of how few realistic role models young boys get,” says The i Paper lady. This is a regretful situation, she implies. This is why things are the way they are. Because of a lack of suitable role models in the classroom, and at home, and everywhere else too, boys are turning to harmful male influencers to learn how to be a man.

“Why do role models for youngsters have to be the same sex as they are, anyway?” said Robert Crampton, a couple of weeks ago in The Times2.

“Many of my best role models have been women. Many of the men I’ve been invited to emulate weren’t worth the effort. For many years (like forever) girls have perforce, had to follow mainly male role models if they wanted to pursue a career in business, finance, science, engineering, much of the arts. Boys would now be well advised to similarly look for guidance across the gender divide. The skills and values they need to lead a happy, productive adult life will be in abundant supply among the female teachers they meet every day”.

I come across another headline. ‘Adolescence doesn’t have an answer’. But Jack Thorne, who co-created it, does. Yes, role models can have a huge impact, he says, but this problem demands a much more radical solution. “We've got to change the culture that they're consuming and the means by which our technology is facilitating this culture”3.

I decide, I will attempt a headline. ‘Mother of daughters speaks out on Netflix drama’. Because isn’t that why I’m here, to stand up for MY underrepresented adolescents? I have no sons. I will never be a #boymum. I can only worry about other people’s. But really. Toxic masculinity may have been turbocharged by the technical advances of the internet but isn’t this just the latest arena for it to thrive. Misogyny doesn’t restrict itself to social media. It plays out everywhere, and Jack, one quick question, how do you think you change a culture?

And I will point him to a mother who says, “Why did he pick you?” when her accused son chooses his father to be his ‘appropriate adult’, whose only comment about her is that she “can cook a roast”. And I will point him to a newspaper that says female teachers aren’t realistic influencers. And I will point him to his ground-breaking drama that lacked robust and identifiable female characters, bar perhaps, the independent psychologist, who has to deal with a creepy security guard who thinks he can do her job. “What is masculine?”, “What does being a man feel like?” she asks Jamie. Is it only being able to control woman?

And I will say that my conscience is no longer able to endorse places, including religious institutions, where my daughters will be kept down, devalued, disrespected simply because of their gender. I am tired of it all. Because this is where it begins, in the insidious, perpetual, drip-drip cultural messaging that says women are lesser, that treats them like pawns in some greater game, that exists inside families, inside churches, inside workplaces, that seeps out into society. And this is where that messaging ends, in incels, in cruelty, in revenge, in Jamie. Fix that, Jack.

And I will point him to a photo of my daughter and say there’s a role model. Start with respecting her.

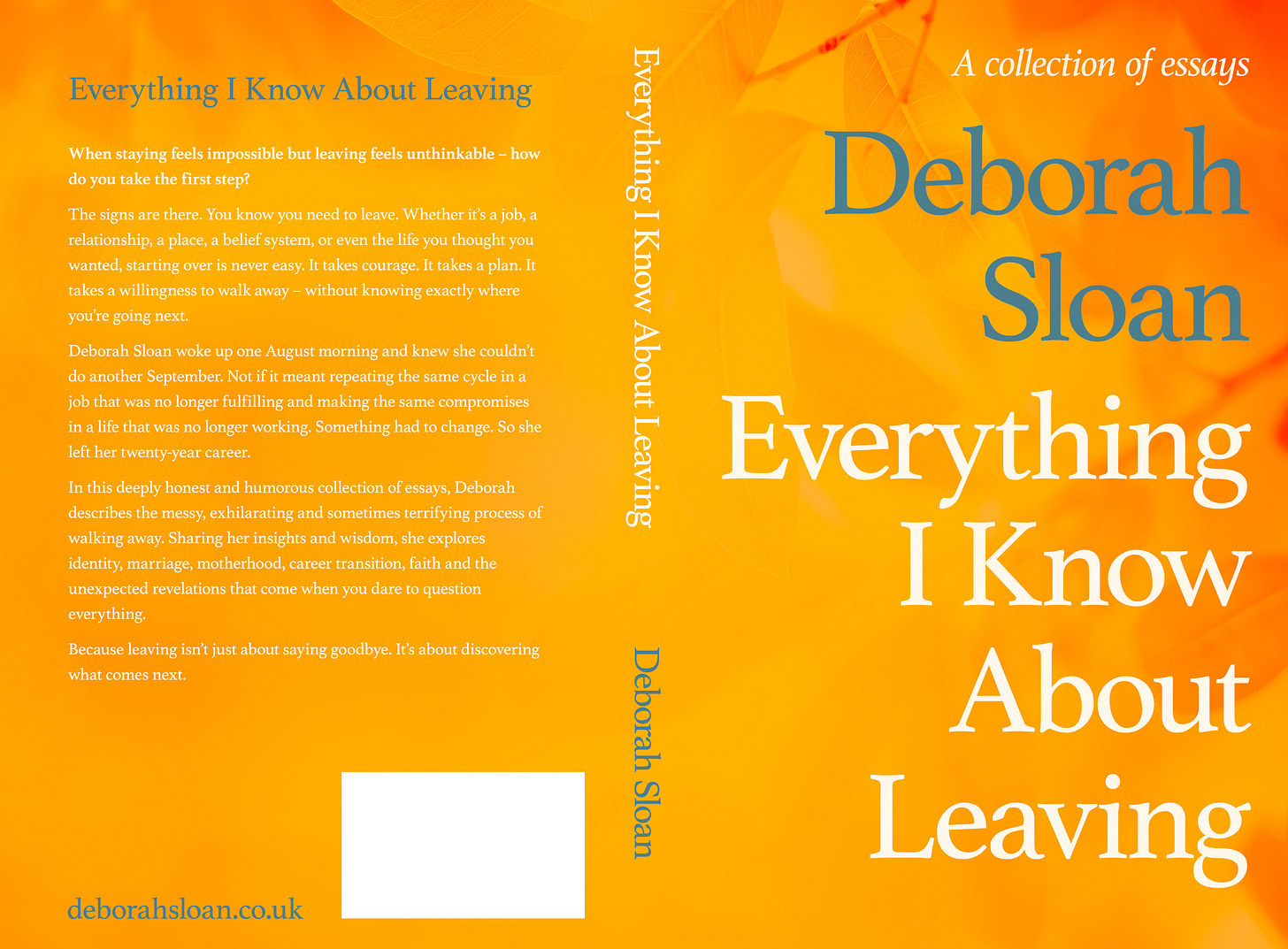

If you’d like to support me, I have the option to buy a copy of my book for £12.99 (includes postage and packaging) via PayPal.