Life, Death and Succession

Hello everyone, here I muse on the HBO series amongst other things...

On Tuesday night, I couldn’t get to sleep. I was possibly over-caffeinated or suffering from post-traumatic Succession1 stress or the aftermath of dealing with death admin, but I was definitely over-processing. I’d got to the end of a chapter of my latest read2 about a middle-aged professor who becomes obsessed with a younger colleague. She is conscious that her time to find success is running out, furious at her lack of it. She is desperate to hang on to her looks. I’d said my prayers, turned off the light, left my diffuser3 to do its thing but the thoughts wouldn’t leave me alone.

That morning, we’d finalised our will. We’d dipped into mortality, discussed power of attorney, executors. It felt very grown-up. I’d said to the solicitor and the solicitor’s assistant who witnessed my signature that I hoped they got outside to have lunch by the sea. Doing wills every day seemed even worse than looking in mouths. They deserved a break. The sea was on their doorstep. It was shaping up to be a glorious May afternoon. They said they wouldn’t have time. As we left the darkness of their offices and got outside, my husband took my hand like he was glad he still could. I kissed him goodbye at the butchers, left him to sort pork chops for tea. We went our separate mundane ways. We’d reunite later and eat meat and salad and garlic potatoes that he’d spontaneously selected as an additional surprise for me. We’d enjoy a BBQ on a sunny evening, I’d talk, he’d listen. I thought about the solicitor and the solicitor’s assistant and mortal coils and reckoned we needed to make time for the sunshine because it never lasts long enough.

In the final ever episode of Succession, Matsson, a Swedish billionaire, who epitomises worldly success and whose money has given him the power to control the happiness of others, had told Tom who craved worldly success too but was only an in-law, “so if I can have anyone in the world, why don’t I get the guy who put the baby inside her, instead of the baby lady”. He’d decided Shiv although she had the right bloodline credentials was too smart, too pushy, too woman, too pregnant to be his CEO. The wife is side-lined. The husband gets the gig instead. It was brutal but real. I’d found it quite hard to be a baby lady.

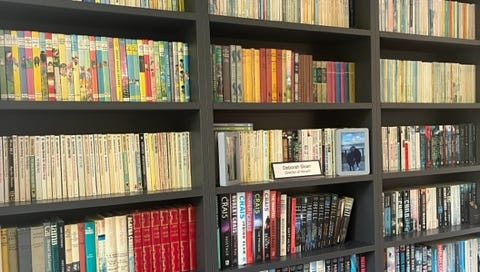

At 1am, I remembered I hadn’t told the person that I was leaving my books to that I was leaving my books to them. I was giving someone a burden they hadn’t asked for. It could be the opening scene in my novel that I hadn’t written. At the reading of the last will and testament (which doesn’t actually happen, the solicitor said I’d watched too much Knives Out) someone discovers they’ve been bequeathed a library. I hoped to get round to writing that novel, that scene. At 1.05am, I determined to start a project, so I’d at least leave a legacy of some sort.

I thought about success generally, how we measure it. I reckoned other people always seemed to be doing far better than me based on how social media measured it. Someone on LinkedIn had got a certificate for something, an accreditation or a qualification, a document really. Lots of colleagues from her organisation gave her a thumbs up. She was getting far more likes than my writing ever did. It didn’t matter what she’d achieved. It could have been a fifty-metre swimming badge, but she had a mutual appreciation society and I didn’t. At 1.20am, I thought about how soul-destroying it is to exist in a validation vacuum. That was all the Roy children had wanted from their father in Succession, an acknowledgment of their worth. “I love you, but you are not serious people,” he said. They couldn’t earn his respect.

In Succession, Connor Roy, the eldest son, who had enough wealth to try his hand at everything yet still couldn’t succeed at anything, had presided over a ‘sticker perambulation circuit’ in his dead father Logan’s apartment where the top-tier mourners and then the second-tier mourners could attach stickers to the heirlooms they’d like to claim. The system to distribute the teaspoons and statues and silver candlesticks was too complicated to process but I realised how much stuff dead people accumulate and that no-one would want my books because they were only important to me. They were my memories and I’d take those with me. Then, Tom stuck a sticker on cousin Greg’s forehead because he was keeping him in a job as his assistant, now he was CEO. He owned Greg. And I was kind of glad that nobody owned me and I’d rather have that than a mutual appreciation society.

At 2am, I wondered whether I should organise my books into a hierarchy. First editions might be of interest to someone.

In Succession, at the vote to determine who wins some acquisition deal I didn’t really understand and where they were tallying who was for and against, and which seemed to be the same as some other vote back in another season which made the business world seem quite boring generally, Shiv reneged on her agreement to back her brother, Kendall as CEO. “I don’t think you’d be good at this,” she said. It was true. He wasn’t a leader. She was honest in a slightly machiavellian kind of way. I reckoned too many people look like a success on paper because they have a title or a position or a role but they’re not really one underneath because they’re no good at what they do.

At 3am, I felt guilty again for having two dirty martinis on Bank Holiday Monday and then sleeping for the rest of the afternoon. “It feels so decadent,” I said to the waitress as I deliberated over the first one. The second was easy. “You only live once,” she said. In Succession, Roman Roy was sitting alone at a bar, sipping a martini, the kind I like with a big olive. That was success, letting it go, watching the world go by, knowing you don’t need what it offers you. But then he was the one who never really wanted it in the first place. Shiv Roy is in the car with her usurping husband, coldly placing her hand on his because she has no choice now. He owns her as well.

The reviews said Succession was a Shakespearean tragedy. They just weren’t sure which one – Macbeth, King Lear, Richard III, Hamlet. It didn’t matter because there was no happy ending in any of them. The finale was devoid of sunshine. We were meant to see that money and power and ambition and greed and success corrupts, that possessions are worthless in the end, that promises mean nothing unless they are kept. “Dad promised it to me when I was seven years old at the Candy Kitchen,” says Kendall, as he tries out the CEO chair. But in the final scene, he is broken. As he wanders through Battery Park, he has lost everything including his self-respect. The only man his father ever respected, Colin the bodyguard is tailing him not because he loves him like a son but because Kendall owns him, that’s his job.

It was Biblical in my opinion, a wake-up call to us all, one I’d wake up and think about on Wednesday morning, after I’d eventually stopped processing and fallen asleep.

What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul?

Vladimir Julia May Jonas

Neom Wellbeing Pod Mini

A great read. Hope you got some sleep in the end.