“What’s the obsession with Yoko Ono?” I said as we crossed the Millennium Bridge. There were banners of her everywhere. She was younger, sans sunglasses, her eyes visible. She was brandishing a glass hammer. As I looked at the solitary chimney of the converted power station, I wondered why they’d put the main entrance round the side rather than overlooking the Thames, but the extra walk didn’t matter because our entry slot wasn’t for another twenty minutes and we’d all the time in the world.

But there was no sign of the screaming woman, not on the list of exhibitions, not on any of the displays, not on any of the walls. There was just more Yoko Ono, and something called Capturing the Moment. As I reached for my phone to check the tickets, I said, “Russell, is there more than one Tate in London?”. And he said, “don’t worry, I’m sure you’re not the first and I didn’t know there was a Britain as well as a Modern either and we can fix this and if we nip round the corner, we can hail a cab and we’ll make it”. And I’d never hailed a cab in my life. And I had no idea where we were now or where we were going or how long it would take but I didn’t ask any questions and I sat in the back seat and relinquished control and looked for signs for Victoria and I thought today, you’ll be the prince and I’ll be the princess1.

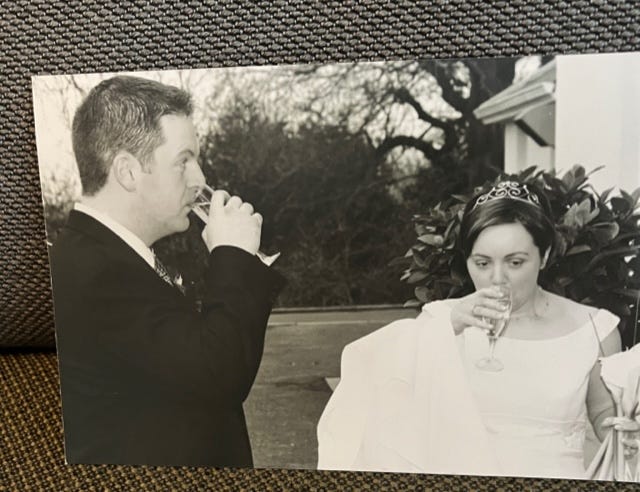

It had been a series of disasters, our 22nd wedding anniversary trip, a portfolio of setbacks. There was an air of doom hanging over it. It was no fairy tale. As we’d exited our delayed Airbus A320, the one with technical problems which sat on the tarmac in Belfast for two hours and then landed in a field somewhere to the left of Heathrow, he said “thank goodness, no more baby man”. Because we’d heard “four months” on repeat from the father behind us as every woman stopped to admire the tiny bundle on his lap. “Is it her first flight?” asked the cabin manager. “Second,” he said proudly. They’d flown over the day before because they’d been working that night. “Do you think they’re in a band?” I said. “Maybe he’s a hitman,” said my husband. And I laughed because sometimes he does that, makes me laugh. We were too late for our pre-booked walking tour round Trafalgar Square, so I’d executed Plan B, and I’d been the prince and he’d been the princess and we’d headed towards Westminster and brushed up on Winston Churchill2 instead. And there was no doubt that Winston was a busy man, but Clementine Churchill was his priority, his trusted confidante. He called her she-whose-commands-must-be-obeyed. He said marrying this clever, formidable but complex woman had been “my most brilliant achievement”.

Last year as we celebrated our 21st, I’d written how after children, there is marriage again3. I’d questioned if we were prepared for that, if we’d salvaged enough of us from the last two decades.

“We never talked about what our life would look like together – how we’d balance babies with careers. We fell into a naïve ideal of what marriage would be. We were ok, sure we had a joint account for bills. I became angry. I’d tell my husband many times that those first ten years weren’t what I had signed up for”.

And those children wouldn’t leave us alone. From 350 miles away, we’d broken up their fights, watched footage of possible GBH, dealt with persistent teenage-hormone-fuelled rage. In a moment of brief respite on a Thursday evening, I’d enjoyed a vesper martini4 because I’d always wanted to try one since Rebecca walked through the train towards her death in This Is Us, reliving the relationships that mattered most in her life and drank one before she was reunited with her husband Jack in the final carriage. “You did good,” he told her.

When my husband woke on a Friday morning, his tummy was doing somersaults and he watched me eat eggs while he chewed on dry toast. And in his Monday conversations, I’d hear him share his weekend with his colleagues, joke about marriage being in sickness and in health and how “Deborah hadn’t expected that to mean when we’d wine bars and ABBA Voyage to get to”. And I heard him because by that stage, I was unwell too and I found it soothing to lie on the sofa and listen to his voice and I thought of Rebecca again and I said, “I’d like you to pour me a vesper martini and talk to me on my deathbed”.

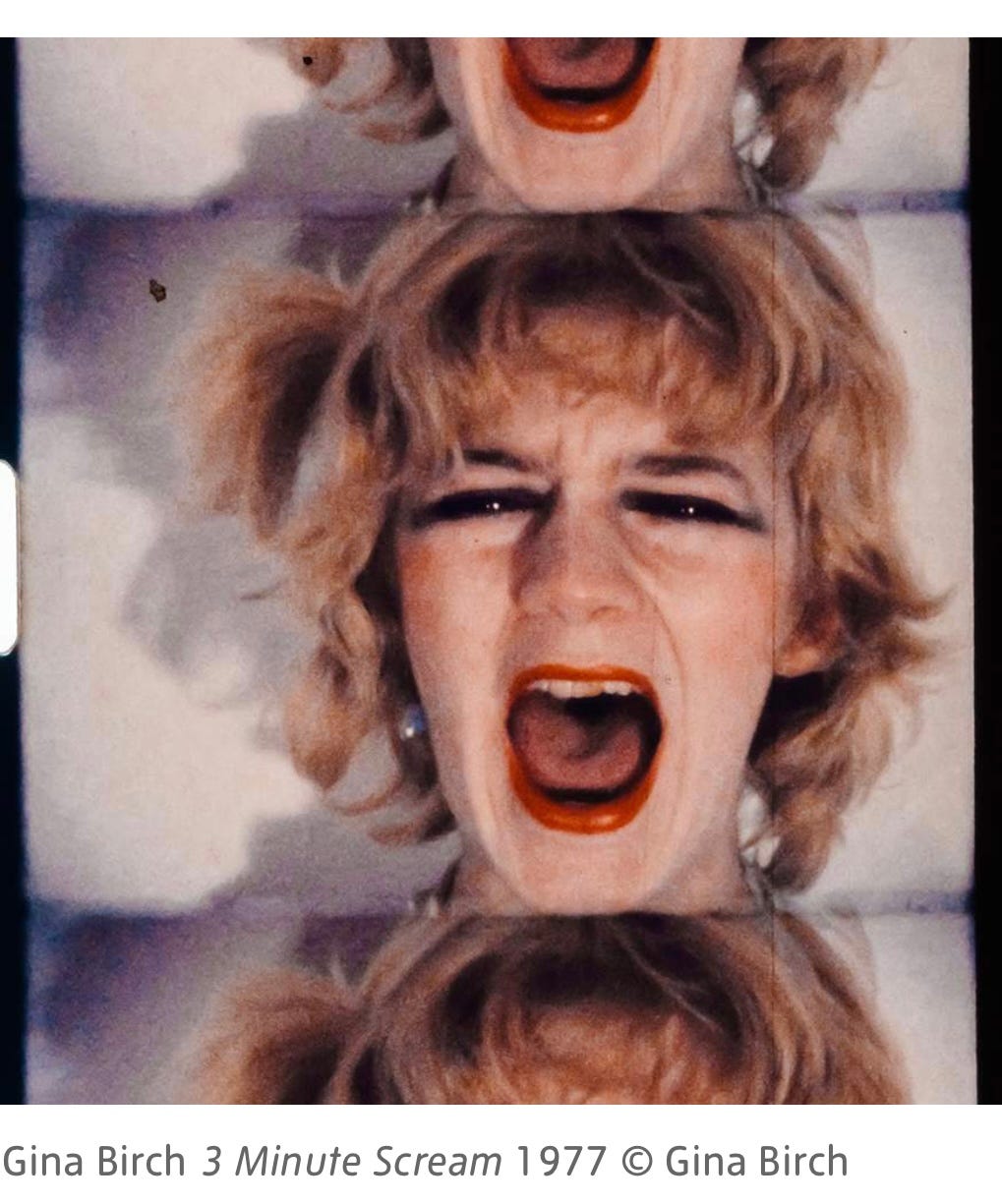

At the other Tate, there was no sign of Yoko Ono, but there were banners of the screaming woman everywhere. And I lost him as soon as we went in because I was immediately captivated by Miss World protests and Reclaim the Night marches and images from Greenham Common and the Miners’ Strike and how brave women used their art to fuel the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s and 80s. And he wasn’t quite so into it, maybe because he was a man and I was a woman or he was in sickness and I was in health. When I found him at the exit, he said he couldn’t cope with the screaming anymore. “But she only screamed for three minutes,” I said. “On a loop,” he replied, and I realised I hadn’t heard her after a while, like how we no longer hear our own screaming after a while. I asked him if he’d seen the daily schedules of the women who worked in the metal box factory doing paid shifts on the production line and unpaid shifts at home, and the photograph of the woman in conversation with herself and the painting of Mother and Child at Breaking Point, the rigid mother with the dead eyes, holding the writhing body of her howling child. There was no baby man to help her, no one to lift the burden on to his lap. There were no princes and princesses. There were no love stories. “Is There Life After Marriage?” it said on the picture of the bride with her hands plunged in the sink doing the washing up. Had anything changed in almost sixty years asked the Guardian5?

Despite using their lived experiences to create their art, these women were left out of the artistic narratives said the blurb for Women in Revolt6. And I thought about Yoko Ono, who was mainly known as John Lennon’s wife, or the Japanese weirdo7 who broke up the Beatles, but rarely as an artist and an activist in her own right, who in a gesture of solidarity with the Women’s Movement had filmed herself struggling to break free from the confines of her bra. Her glass hammer was symbolic. It could not break anything without breaking itself. And in December 1980 after the sudden brutal ending of her love story, she began to wear dark shades to hide her eyes, to put a barrier between her and the world.

When I’d talked about our marriage before, I’d said I didn’t want to write some ghastly love story, that I didn’t have the secret to a happy marriage but as we’d sat waiting on the tarmac, I’d been struck that marriage may simply be the ability to deal with setbacks whilst sitting together in companionable silence. But as the flight departed, I’d read an article about the 60/40 principle. “Marriage is never 50/50,” it said. “If both partners instead focus on giving 60% and taking just 40%, the relationship has an overwhelming chance of being successful”.

I thought of Rebecca and Jack, Yoko and John, Clementine and Winston, how they prioritised each other, their 60/40, how each gave more to the other than they took. And I guess that’s a love story.

P.S. You can listen to me in conversation with me on my podcast – The Episode on The Women Load…

Taylor Swift Love Story

After Children, There Is Marriage Again

Sometimes we talk about the ones that have left us, passed away, moved on to glory. I was fond of Uncle Norman who grew too many tomatoes. The crop he was so proud of was a great reason to turn up on people’s doorsteps and invite himself in for lunch. He appointed himself unofficial photographer. We’d get an album a f…

Well you didn’t tell me all this last Sunday!! I have smiled and laughed a lot whilst reading. Certainly never pictured Russell as a princess. Sounds like you fitted a lot into your break even through sickness and through health! Happy anniversary and I trust you will be kept laughing for at least another 22 years. That last photo is definitely very warm and fuzzy 🥰