On the morning of the launch, I said to my husband that I felt like I was getting married to this book. That was the last time I’d lost my appetite, my wedding day. Almost a quarter of a century and a lot of resentment had passed under the bridge since then. This was a major life event, a realisation of something I couldn’t quite name, an ending or a beginning, a miracle perhaps, a culmination of all those childhood dreams looking at the authors on my shelves and wondering if I too, could be one.

And in addition to this major life event, this significant milestone, this emotionally charged occasion, I had added a physical event, one where I had a lot of practical things to sort. “It’s an event on top of an event,” I said to anyone who would listen. I remembered the horrors of event management, the checklist, the being pulled in multiple directions, the sick feeling, the problematic room layouts, the technology, the sore feet, the don’t forget the tablecloth, the why is everyone arriving at once, the crash when it’s all over. I’d packed Birkenstocks, a spare pair of tights, a mirror, two pens and another pen just in case.

“Do you know it’s my book launch tonight?” I wanted to say to the trainee pummelling my head over a sink in the hairdressing salon. “Is the temperature ok?” she’d asked on repeat. “Perfect,” I’d said as she scalded me. She was now attempting a massage. I could feel her kneading me, my brain shaking, my neck breaking. “I’ve a speech to give,” I thought. I absolutely have to be able to form sentences. I was ticking off the essentials – blow dry, nails, outfit, eyebrows, pick up the non-alcoholic option, check with the venue that they’re still expecting me. I was mainly concerned about the drinks’ situation. Would there be enough glasses? I had no idea how many were coming. I’d abandoned RSVPs. I gathered all the breakable ones I owned, bought thirty-six plastic flutes from Sainsburys, dug out a few other disposable options from the back of a cupboard. I reckoned I’d done my best. There was a backup for the backup.

Then there was the admin to manage. “I’m not coming”, “I’m coming a bit late”, “I’m coming”. And on a Thursday in March, in a hazy daze of anxious anticipation, in between sending WhatsApp replies, I set books on doorsteps and posted them through letterboxes. I said sorry to the person whose copies I’d left in their recycling box but confirmed I hadn’t inspected their bottles. I opened an envelope that had been posted from Stratford-upon-Avon. My pen pal of almost four decades, the one I’d first written letters to in the 1980s and now sent messages to on Instagram, had made me a special card. There was a typewriter, the title ‘Everything I Know About Leaving’ peeking out of it.

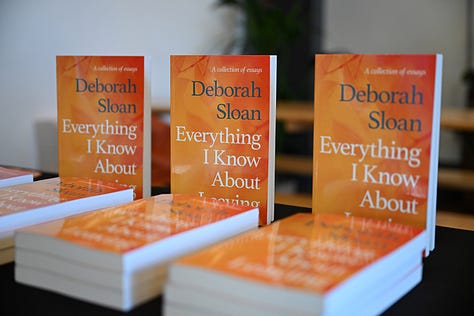

And at 5.30pm, having dressed in black to disguise any nervous sweating, I found myself alone in a taproom and I felt it, the loneliness, the vulnerability, the fear. I spread the tablecloth. I unpacked my books. I set out the napkins. I waited. Two men watched me as they drained their Guinness and reminisced about the 1970s. I willed them to read the sign. “All tables needed back by 5pm”. I took pictures of the strelitzia, of the chamaedorea elegans, of the epipremnum, of the other plants I didn’t know the scientific name for, of the funny little purple door that might provide an escape route later, of the sun streaming in and landing on what could have been an original Edwardian floor and I realised I was standing in the shadows of the past, on ground that had once been a spinning mill, a place that gave women employment and a status, a place ahead of its time.

One of the men burped. It seemed to be their signal to leave. I photographed their empties, then returned them to the bar. And I waited.

“That’s one of my favourite songs,” I said when I heard Bob Seger playing in the background. This is, I thought, definitely a sign from the universe. It was all going to be ok. “And my soul began to rise,” sang Bob. “Is that not your playlist?1” said one of my daughters.

But over the next hour, something did happen to my soul, and it happened when Michael showed up with his camera, when Alan appeared with his sound desk, when Lee arrived with his questions, when Pete delivered the pizzas, when I saw how many people had turned up to support me, when I realised I was part of something so much bigger than myself, a community.

“All those likes and comments and emails really matter but what I love most is when I bump into someone, and they unexpectedly tell me something I’ve written has resonated. Resonating is what it’s all about,” I said as I perched on a stool and clasped my mic and felt my life flash before me.

There was a sea of faces, faces that represented the breadth of relationships that had made up my life’s journey, the school mums and the school dads, the support systems for my four children. We’d been a team, navigating P1s and Year 8s and the start of the university years. My church friends were there. Emma and Julie and Alison from my first book club were there. There were at least two ministers, a principal, a GP, nurses, solicitors, business owners, many who worked in the IT sector, fellow creatives. Joy had travelled from Derry, Ali from Coleraine, Maureen from Newry, Bethany from Sligo, Tone from Heathrow. I didn’t know which was furthest in terms of mileage or effort. There were people I’d never met in person before, subscribers to my ‘Friday writing’, Emma who had shared all her publishing knowledge with me, connections from LinkedIn who were going through similar career transitions. There was Caroline who reminded me that we’d made her a lasagne when her baby was born. There were former colleagues, ones who’d moved on, others who were still holding higher education together.

The world needs "life-changing books," said Ann Patchett.

“Are you conscious of giving people a more optimistic view of humanity?” Katty Kay2 asked her. “No,” she said. “It’s the world I see. I look out through my own eyes. If I’m reading the news, I can see lots and lots of horrible things. But the people that I interact with every day are really kind people. Every day. The people I work with at the bookstore, the people who come into the bookstore, the people I see in the grocery store, the people in my neighbourhood. There is so much kindness, decency, thoughtfulness that I don’t see represented often enough”.

“Yes,” she admitted, “maybe there’s more kindness than you might see in other books but not more kindness than you might see in your daily life”.

A few days later, I went to someone else’s event, one where I could just turn up and sit down and listen, one where I didn’t have to bring the tablecloth. “It feeds my soul,” said the man called Christopher, who took photographs of strangers on the street3, who had conversations with them and shared those interactions with millions of others. There was no rationale to the subjects he chose, he said, other than he found them interesting. He was drawn to his models. Somehow, whether intuitively or divinely, he picked out the people who needed to be picked out. He told us to watch how their faces changed as he engaged with them. “I just thought that you had a really cool look”, “I think you look absolutely lovely,” he said. He admired their outfits, their styles, their smiles. He told them he found them interesting. And they lit up. “I tell them I’m just like them,” he said. He’d come across Nan on her birthday. She’d had lunch by herself. “I do that all the time,” Christopher said. Josephine had never married. Her best friend had died two years ago. She’d been an only child. “I’m an only child too,” said Christopher. She would be on her own at Christmas. She hated being on her own4.

“I regard myself as the greatest failure that ever walked the planet earth,” said James. “I call myself the Could-Have-Been Man”.

“Practice any art . . . no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow,” said Kurt Vonnegut.

And something in James changed as he posed for his portrait. Through his art, Christopher found the lonely and the low. He saw them and he brought them back to life again. And it fed his soul too.

Ann Patchett had only found commercial success with her fourth novel. Katty Kay asked her why she hadn’t given up. “Many people who had written three unpublished novels would have,” said Ann. Success wasn’t what she achieved with them. It was simply putting them out into the world. Failure would have been an unwritten book, she said.

The day after the book launch, I posted an update on social media.

“Writing this book was never really about me or being something. It was about saying something that resonated with people and bringing them together,” I said.

“I am not all books, but I am this book,” said Ann.

She looked out through her eyes and saw a world. Christopher looked out through his and saw a world. And I looked out through mine and saw one too. And we shared what we saw. Humanity. And it made our soul grow.

BBC Influential

To see how Josephine’s story turns out, visit:

Well done you ,resonate is a great word , takes me back to when (and still do) I gives speeches of political content , the writing ,editing ,re writing ,standing in front of a long mirror practicing ,calming down ,flying or driving in the winter months ,reaching the venue and going into focus mode ,how many will turn up ,what happens if only a few souls attending out of curiosity ,nervous tension when a surge of people suddenly turns up ,slow down breathing and go for it ,hoping they understand my soft N Irish verbal voice tones , suddenly it is over and check how many are clapping and did I resonate with the audience , quick need a cup ot tea !!!

A great night for a great book written by a great woman! Enjoy your success Deborah. I’m on route to the US and it’s in my bag ready for the holiday reading.