“Is there anyone at all?” she said. We had exhausted the list, the pool of senior leaders, every head of department, the professors and the Grade 9s. In a system that equated rank with success, I was supposed to pick the one I admired most. If they were too busy to mentor me, I could suggest a back-up. We’d engage in a year-long exchange of information in the canteen. They’d look good and I’d look needy. They’d share their knowledge and expertise and I’d understand how to become successful. In an attempt to alleviate the boredom of a job that mainly demanded I turn up and perform a range of functional tasks, I was doing one of those female leadership programmes that promised me lots of notes on how to get a promotion. I’d type them up afterwards and try to decide why I was so under-utilised. I felt sorry for the lady from staff development. I wasn’t easy. But, they were just names and roles and positions. I didn’t know any of them, not in the way I need to know someone before I’ll give them access to my life. They had to deserve it. They had more visibility than me, that was all. They weren’t better, they’d simply played the game better.

The mentors had MBEs and MBAs, they ran meetings and marathons, they wore suits and smiles, had both babies and budgets. But were they funny? Could they manage a room full of toddlers? Did they have something you just couldn’t put your finger on? Did they exist beyond the workplace, chat to their butcher, shop for their elderly neighbours? Would the man from the post office get up and move his friends round the plane so they could sit with their family? Did they whip off their bra as soon as they got through their front door and grab a bowl of peanuts? Did they take off their high heels? Did they take off their personas? Did they have dogs that were devoted to them, children that saw them, people that trusted them? Did they have someone they’d never want to miss the thrill of being near1? That was the kind of success I was looking for. I wanted to catch them unawares in the supermarket, nosey in their trolley, make sure there was no boxed wine, see them help their octogenarian parents in and out of a car, believe they had the capacity to not just email but dance like no-one was watching. I’d even considered a man. I liked the man with the doctorate and a bank of research papers who had come to a leaving do for someone beneath him on his way to dinner with his wife. They were already squiffy, giggly, in love. He was on the cusp of retirement. I was glad he had something else to show for the last forty years.

“There is someone,” I said. I wanted the woman who had lost her title in a restructure, who had been demoted, who was a grade lower than me now. She wasn’t on the list. She was angry. She hadn’t forgiven anyone. She had a file on the people who had done it to her, all the emails they’d never answered. When I too was shafted, she was the one I called. I didn’t want to know what it felt like to have success, I wanted to know what it felt like to lose it. It took me five years to finish the process of choosing to lose it, to reject an organisational system that told me I had to be something to be someone. When I left, I didn’t bother to tell the boss who was busy trying to be someone. He didn’t bother to wish me well.

When we (metaphorically) brought the women we admired to the female leadership programme, I brought Claudia Winkleman. She was funny without even trying. She could be both cynical and charming. Her and Joni Mitchell2. The female leadership programme provided role models who promised to tell us how we could imitate them and get a promotion. I didn’t find them funny.

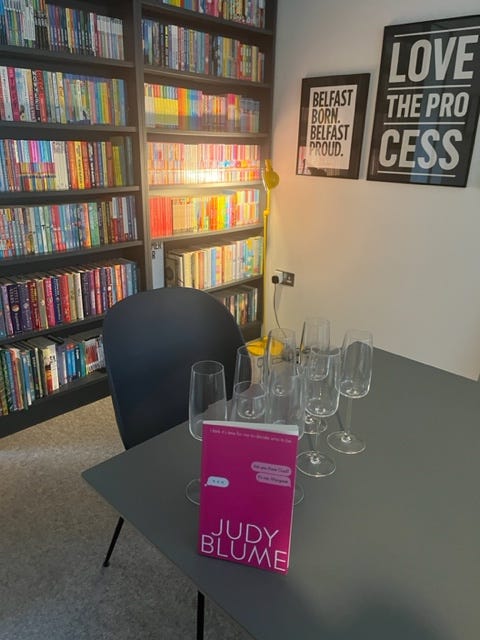

There were nine of us round a table last week. We had a collection of daughters between us. We had sons too. I’d contact everyone afterwards to say what a relief it was to be in the company of funny women. I’d been worried there were only dull corporates left in the world, walking clichés. I’d been spending too long on LinkedIn. I admired their naturalness, their ease, their articulation, their truths and their lack of interest in being promoted. I was especially pleased with my canapés. I’d had the idea and my husband had implemented it. We were a team. I’d filled their glasses, lit some candles in honour of Judy Blume. I thought about what my former employer said BRAVE was, how I needed to demonstrate it to get a promotion. But there is nothing braver than being banned. “You can write,” Judy’s husband told her, “as long as it doesn’t get in the way of looking after the children”. Reader, she divorced him, found someone else who shifted their life to accommodate her desires. She got herself a better team. If Judy Blume had been in my organisation, I’d have begged her to be my mentor. Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret had been written in 1970. We were trying to figure out who our daughters should be reading, listening to now. We wanted them to have decent role models. We were just their mothers. Maybe it would be us one day, but not yet. We wanted them to know themselves. We wanted them to value their minds. We wanted them to not just love their body but to love with their body3.

I could make a list, seek them out, the role models they could read and listen to. If the words weren’t there yet, I’d write them myself. I could go to Lisbon to do it. I’d been looking at a course, five days in September. I wasn’t sure if I was brave enough. I’d refreshed the page, searched flights, picked a hotel, I could avoid the fado so I didn’t have to walk anywhere in the dark. “You can’t go on another holiday,” said my fifteen-year-old, “I have important exams, I need stability”. But I need her to know that de-stability is what I desire. If I missed the first day of term, I could be sent the photographs rather than take them. I was interested in how to be that non-guilty mother, how to pass the best gift of all on the next generation, how to role model that my dreams matter. It had perplexed Deborah Levy4 too. She was trying to pitch a female character to three film executives. She was based on a male character, the father-writer in Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly.

“She follows all her desires, every single one of them. She is ruthless in pursuit of her vocation, takes up every offer while her family pine for her. Furthermore, … she has many affairs with people she will never fully commit to and she always buys her children thoughtless, last-minute presents at the airport when she returns from her exciting travels”.

They laugh, the film executives. “I guessed that no woman around that table had ruthlessly pursued her own dreams and desires at the expense of everyone else,” Deborah says.

I wondered was that what a decent role model looked like. Is it about promoting myself to what I deserve and letting people see me do it?

For homework… if you feel like promoting yourself to what you deserve, have a look at the footnotes. Read them, listen to them. And if the words aren’t there, write them yourself.

No More Lonely Nights Paul McCartney

Both Sides Now Joni Mitchell

Glennon Doyle

Real Estate Deborah Levy

Great piece! I found it challenging not having more childfree role models. As well as those who define success on their own terms. I guess there are the words I need to write!

An excellent piece of writing, Deborah.