One of Belfast’s most famous streets was the main route between our houses. She lived near the bottom with her granny, I lived near the top. There was a class system and a lot of trees in between us. My house didn’t just have a number, it had a name. Her’s had a backyard and a bathroom off the kitchen. I’d try to pee quietly because someone was always topping up the teapot. I played tennis, she played the accordion. We weren’t that into Van Morrison. We’d only heard of him because her mum lived at the far end of Hyndford Street. He wasn’t going to be blu-tacked to our bedroom wall. He’d gone a bit spiritual. Brown Eyed Girl1 was a song old people liked, Cyprus Avenue was where the Larmours and the Reynolds and Ian Paisley lived, where our church was. She’d walk half way up it with me until the time a man slipped out of a car and asked me where the massage parlour was. After that, she walked me the whole way home. She was bigger than me.

We went to a school that finally called itself a grammar in 1993 in order to avoid confusion with the one Van wrote a song about next door. Both of us were anti-social, we had friends in our form class we could just about tolerate. She was in G, I was in R. I had an intense fear of God, she had an intense fear of her mother. We’d bonded over GCSE German, our aborted trip to Stuttgart when we realised we weren’t learning the language, we were staying in an apartment with a psychopath. I’d squeezed her into the phone box behind me, called a land line, explained we needed an urgent flight home. We were sixteen. As we waited in an empty Kuwait Airways departure lounge with hundreds of dead flies, the Gulf War was starting. Neither of us can believe we’re this old, that we’ve been through so many wars. We’ve finally found a hairstyle that suits us. We’re still trying to avoid the people we went to school with. It’s hard, a lot of them hang out in Ballyhackamore. They’re the ones Kenneth Branagh talks about, the ones that stayed. As I lay in a hospital bed in my twenties with an unusual rash, the newly-qualified doctor asked me had I seen anyone from school recently. In my thirties, a fellow mum at ballet reminded me that I was posh, my parents had a breakfast room.

“Where are you from?” asked the former magazine editor with the huge Substack following when I booked a mentoring session in an attempt to figure out how to move my subscribers into double figures. She was struggling to place the accent. “Belfast,” I said. She was excited, suddenly animated. This might be a lead. She’d found something vaguely interesting about me. “You could build a community around that,” she said, “where you come from”. “There’s a guy in Manchester has done that really well with Mancunians”. I wasn’t sure she understood what kind of people we are, that we have plenty of communities. I didn’t think coming from Belfast mattered that much to my writing. Nothing will beat that descent into the city at night, Cavehill on the right, the Lough on the left but I don’t reference it much. The ‘Troubles’ were the backdrop to growing up in Northern Ireland but they didn’t eliminate all the other teenage traumas, the angsts about what to wear, being in or out, boys, spots, the fact that I was never going to look like Kylie Minogue. And anyway, Lisa McGee has already done my past. Derry Girls has already said it all.

I want to write about the universal experiences of humanity not about the ‘Troubles’. They were always there in the background, often in the foreground but they aren’t my whole story. I disagree with Paul McVeigh. Rich people weren’t spared the ‘Troubles’.2 I’m not even sure what he means by rich people, those who lived in the suburbs? None of us were spared it. When Simple Minds, Spandau Ballet, The Adventures sang songs about us, I felt seen. We were isolated. Music and writing mattered. U2 never abandoned us. No-one will ever write better stories about the consequences of religious division than Joan Lingard. I was delighted when Stephen Hendry came to play snooker in the Antrim Forum.

I pondered the former magazine editor’s advice. I’d call my Substack ‘Days Like This’. There’d been that concert in the 1990s. Van was there wailing with Brian Kennedy. Everybody was a bit emotional, hopeful about the future. This could be the turning point, they thought. I was somewhere near Primark. Bill was very far away, a speck in the distance. I was wearing a cream Dorothy Perkins jacket. I was doing an arts degree and had a job in an insurance company three days a week. I spent most of my salary in Next. Van was the honorary guest at my graduation a year later. He refused to speak, fell asleep in the Whitla Hall. I still saw Julie from time to time, called round for a cup of tea in the kitchen beside the bathroom and a catch up about people we didn’t see. I never had to say I was coming.

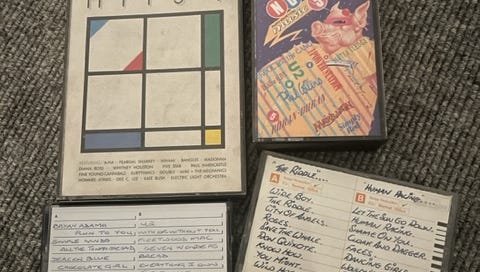

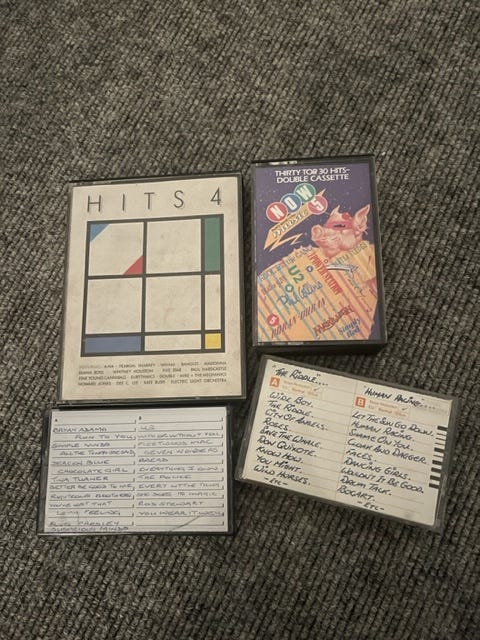

It was somewhere in the middle of swallowing a large plate of sticky shoulder lamb kofta in the restaurant, named after the street or maybe the song, to celebrate her birthday that I realised who Julie is to me, how much being invited into her family had meant to me. “You always had mince on a Thursday,” she said. But I always had pastie and chips with her on a Friday. I’d pick up the phone in her granny’s hall, let them know I was staying a while longer. “Leave a 10p,” my mum would say. I admire how content Julie is, how she hasn’t travelled too far, how she doesn’t need to be on LinkedIn. I’m glad she has found her gift. There are many brides who owe her their wedding day. She is a talented seamstress. I have all the blankets she knit my babies. “Do you remember the cassettes you made me?” I said. She’d find something new, something neither of us had heard of, make me a copy, handwrite the sleeve. She introduced me to The Beach Boys, the 1960s, country ballads. I passed on the heavy metal. I swapped my Billy Idol Greatest Hits for her Joshua Tree. She made me mixtapes. We’d listen to records. 5pm to 7pm on a Sunday night was sacrosanct. We didn’t have a favourite song. We liked them all.

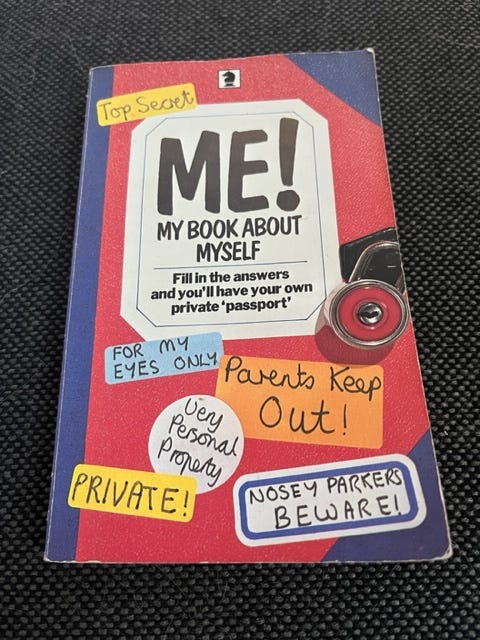

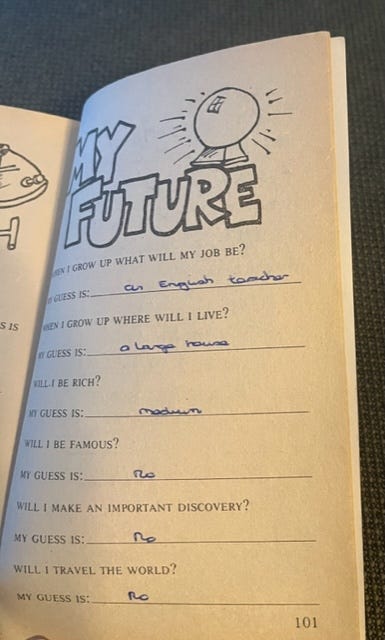

I headed to my plastic box of memories. Among the cassette tapes, there was a book. It was top secret, Me! My Book About Myself. I’d written my answers in the 1980s. At the back, it warned never to throw it away. “In twenty years’ time, you must look at it again and see how many of your guesses turned out to be correct ones,” it said. I didn’t like Thursdays, my favourite country was Northern Ireland, my favourite town Belfast, I wanted to be an English teacher. I got £1.25 pocket money per week, I liked cauliflower, I loved Duran Duran, Alison Moyet, Nik Kershaw. And I still do. Not much has changed, except maybe the pocket money. And maybe we all need those friends who remind us of who we used to be, the ones that demand nothing from us, who simply say Girl, Put Your Records On, Tell Me Your Favourite Song…

“Oh my mama told me

There'll be days like this”…

Playlist – Brown Eyed Girl (Van Morrison), Belfast Child (Simple Minds), Through The Barricades (Spandau Ballet), Broken Land (the Adventures), Days Like This (Van Morrison), Put Your Records On (Corinne Bailey Rae), anything by Duran Duran.

Impermanence https://noalibis.com/product/impernanence-essays/

I love this Deborah. Takes me back to the simple life we had with friends who impacted our lives.

Jonny is reading Bono’s book at the minute so we are having a full on U2 revival, poor boys subjected to all of the Rattle and Hum film last night