It was sitting at my front door when I arrived home on Easter Monday. It must have been left there at some point over the weekend, a special delivery package that I hadn’t signed for. I had escaped the city on Good Friday, not because it was sticky and hot but because I wanted to see the sea and read books somewhere else. As I finished all 384 pages of Fleishman Is In Trouble whilst listening to young men drive old Sierras past my window, I realised I’d been wrong to avoid it for so long. It wasn’t the story of a man discovering Tinder, embracing his sexual freedom. It was all about the other side of the story, the women who can never be free, Rachel’s nervous breakdown, the obstetric violence she experiences, Libby’s stifling marriage, her existential crisis, Hannah’s public shaming, the boy who walks away unpunished. I had risen at dawn on Easter Sunday to reflect on the resurrection, the bigger freedom story. I had watched the sun rise over the town of Portrush where my husband grew up during ‘The Troubles’. Sometimes we’ll talk about our childhoods sixty miles apart, mine in middle-class East Belfast suburbia, his in an isolated row of houses on the back road to Bushmills, how we remember different bombs, how we swapped places occasionally when he came to Littlewoods in the city centre for an Ulster fry and I bought shell ornaments, fed the two-penny slot machines, stopped for a picnic somewhere close to those ominous trees on the way to the coast. We wondered did we ever pass each other in the 1980s and not know. “The big wheel keeps on turning,” I said as I posted shots of Ramore Head on Facebook.

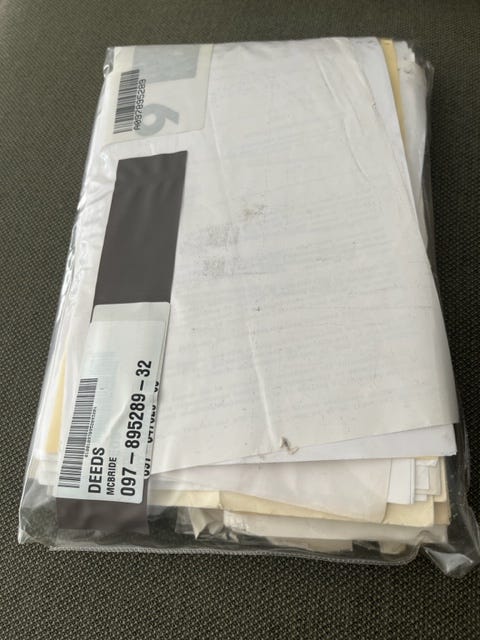

The special delivery was a plastic folder full of documents. It took me a moment to understand its significance, to establish that it contained the deeds to my first house, a two-up, two-down terrace I’d bought as soon as I secured a permanent job. All I’d ever wanted was to be free, to live in a place of my own. I’d completed my twenty-five-year mortgage. It was mine now. It had gone in a blink of an eye. As I pored over its contents, I marvelled at my early adult 1998 signature, agreeing to be the borrower in the presence of my solicitor, two capital Rs, one in the middle of my first name, the other in the middle of my second. I’d lost the second one when I married. I’d allowed my new husband to move into it, but number 8 would remain solely in my name for a quarter of a century. I am still paying its ground rent. I have the grey concrete plaque from outside its front door. I haven’t been inside it for over twenty years. It has tenants now.

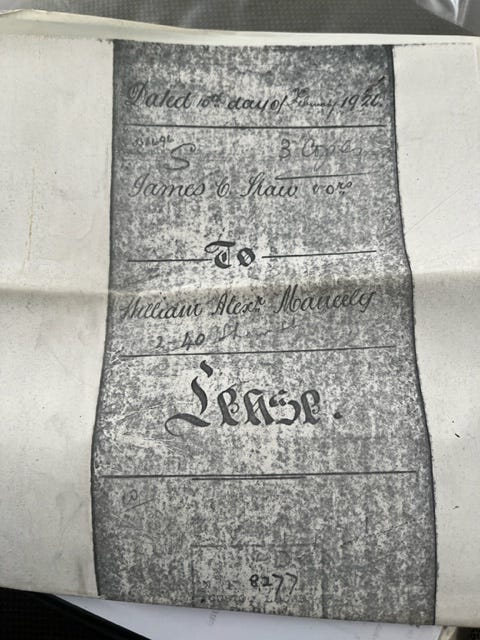

It started in 1920, the history or the future, I’m not sure which, a beautifully handwritten indenture detailing the transfer of the lease from James Colvil Shaw of Trinidad, Tobago, Charlotte Elizabeth Shaw of East Prawle, Devon, Archibald Campbell Shaw of Malta, medical doctor to the builder who would develop the even numbers on their land. The street would be named after them, the odd numbers would come later, more housing for the growing population of Belfast, additional streets creeping up towards the Strand Cinema, built in 1935 in the grounds of Strandtown House, owned by a shipping family who didn’t build the Titanic. There were lots of searches, an application to add a two-storey extension in 1983, a death certificate from 1997. When the vendor and I had argued over a damp proof course, I hadn’t comprehended he had lost his wife just six months earlier. In my immaturity, I hadn’t noticed the two small boys without a mother. I wasn’t a mother yet.

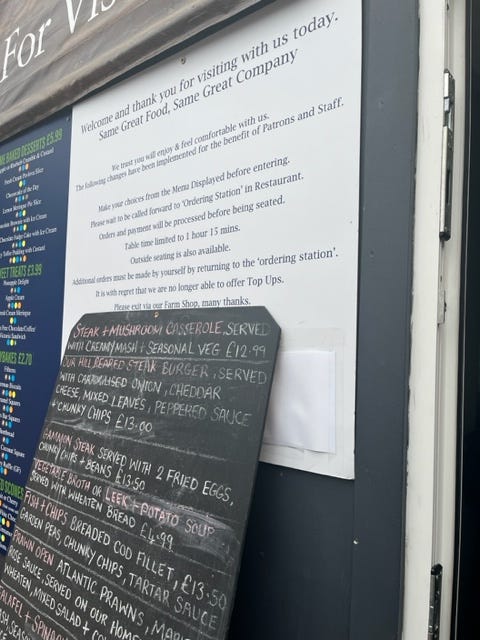

“Did you realise you bought your house at the same time as the Good Friday Agreement?” my mother asked as we sat in a restaurant in the hills overlooking Strangford Lough. I was still processing its rules about lunch. Everyone in the queue had white hair. They’d definitely lived through ‘The Troubles’. Top-ups were no longer available post-covid. I pondered what would happen if we outstayed our one hour and fifteen minutes. I wondered when Sam McKee bought his farm in 1922, with just a few cows to feed his family, if he could ever have imagined people agreeing to so many rules, that five generations later, his food emporium would be feeding most of Northern Ireland. “No,” I said. I remembered picking a kitchen from B&Q, a sofa from MFI, a small claims court battle over a warped wooden floor. I hadn’t remembered my dad slicing his hand as he laid the replacement laminate, the blood, the stitches. I remembered the first July I’d lived there, the noisy neighbours, the party I’d called the police about. “Madam, do you realise the city is on fire?” said the man who took my call. I remembered Omagh, the summer I’d been hospitalised with an unusual vasculitis. I’d discovered the rash which wouldn’t blanch whilst standing in the bathroom extension. I’d painted its walls purple, put luminous stars on the ceiling. I remembered my sister’s grief because there were pupils she taught. The Good Friday Agreement wasn’t the end of it, the anniversary of that terrible day is yet to come. I didn’t remember voting. Was it an X in a box.

“Would you have gone if you’d still been working there?” my dad asked. I was pleased he thought I’d get an invite. The US President had officially opened the new campus of my former employer. I was glad it had gone well, that there were no technical hitches, that they’d pulled it off after all those weeks of secret conversations with the White House, that so many people enjoyed selfies, that there no major gaffes, that another symbolic moment had passed into the past. But I hadn’t watched it. I don’t know what he said, probably something about history or the future. I’d accidently clicked on some sort of live stream on Twitter as Air Force One touched down. “People can see you’ve joined,” it said. I left quickly. The Met Office had said that heavy rain and strong winds might lead to some difficult travelling conditions. The MD of Belfast International airport wasn’t concerned that this would impact POTUS’s travel plans given that he’d be arriving in a 747. He represented the pragmatic Northern Ireland I love best. I remembered when it was called Aldergrove. “No,” I told my dad. I wouldn’t have broken my Easter holiday.

As I chatted with fellow writers on Substack, the same advice cropped up yet again. “Find your niche,” said the expert on marketing. I’d been told Belfast was my niche, but I just can’t do it, make here what I write about. There are enough words without mine. “Excuse my ignorance,” asked someone who cared, “I guess Brexit really blocked up Northern Ireland. Would Scottish independence help or hinder Ireland?”. I had no idea. I remembered there was a period when it was really hard to get a basil plant. I had to google the Protocol, the Windsor Framework. I checked out the Good Friday Agreement while I was at it. It said the two sides agreed to work together in a group called the Northern Ireland Assembly. I can’t understand why we are so proud of ourselves this week. When I replied, I tried to explain the geography of the island, EU regulations. She thanked me. “I hope all works out for the best in the long term,” she said.

As I walked in temporary sunshine in this place I call home this morning and considered what I would say about the last twenty-five years whilst in temporary possession of deeds which I’ll deposit somewhere else soon and move on from, I thought about the temporality of the Biden visit, how he moved on quickly to his genealogy, how much it had been about him rather than us. I thought about my friend Peter, how he’d been part of the team who had provided all the administrative requirements for the Good Friday Agreement, how he’d also helped me with my house, played the organ at my wedding, how our lives and our stories interweave in so many ways. He’d shared a twenty-five-year-old photo of his colleagues on LinkedIn. “At every major point in our history you’ll find a group of unsung heroes like these who’ve worked hard behind the scenes to help make things happen,” commented the former head of the Civil Service. I wondered were any of them invited to hear the President. Twenty-five years of people working away behind the scenes, making history or the future, I’m not sure which. All I know is that agreements matter. In 1998, there was a Good Friday Agreement and in 1998, I agreed to buy a house.